Progress: Find ways to make people’s work progress visible. This can be a kanban board, checklist, or even a thermometer graphic! Don’t forget to focus on professional development progress as well. Schedule quarterly meetings to talk about career growth and weekly check-ins to reflect on the growth and decide on small steps to take next.

As a part of our series about the five things you need to successfully manage a remote team, I had the pleasure of interviewing Tania Luna.

Tania is the Co-CEO of LifeLabs Learning. She is responsible for business vision, strategy, organizational design, and a commitment to the company’s mission and values. She is also a researcher, educator, and writer for Psychology Today, Harvard Business Review, and multiple other publications. She is the co-author of two books including The Leader Lab: Core Skills to Become a Great Manager Faster. She co-hosts the podcast Talk Psych to Me. Her TED talk on the power of perspective has over 1.8 million views.

Thank you so much for doing this with us! Before we dig in, our readers would love to get to know you a bit better. What is your “backstory”?

It depends on how far back you’d like me to go! I moved to the U.S. from Ukraine as a kid, so I’ve always had the advantage of holding an outsider-insider perspective. It’s one of the things that drives me to equip people with skills and build an organizational culture that enables deep, meaningful connections. I fell in love with psychology and went on to study a wide range of areas from emotion regulation to group creativity to the psychology of surprise, then found my “home” in the world of leadership development. It’s a topic I’m passionate about because I want to close access gaps that exist all over the world to these skills and to excellent leaders who help bring out the best in their teams.

Can you share the most interesting story that happened to you since you started your career?

Every day is interesting! But one particularly memorable experience was teaching a workshop on leadership skills to high school students in rural India immediately after teaching a similar session to a group of executives in a fancy boardroom.

After finishing up with the execs, I hopped in a car and drove for an hour outside of the city. I arrived at the location, which turned out to be a tent with a projector and no air conditioning or ventilation. It was almost unbearably hot and stuffy, and I was worried the students wouldn’t understand me well or care much about the concepts I was teaching. And I was wildly wrong. Compared to the seasoned execs, these students were beaming with enthusiasm and curiosity. They literally leaned forward in their seats, and then gathered around me to ask thoughtful questions about leadership and workplace culture.

It reminded me that leadership is something we can all do in all areas of our lives. And it helped me recognize just how important the tools we teach are for unlocking access to opportunities.

Can you share a story about the funniest mistake you made when you were first starting? Can you tell us what lesson you learned from that?

There are too many to count, but the first thing that comes to mind is my time working as an EEG technician at a neuropsychologist’s office. My job was to do brain scans for patients with brain injuries, mood disorders, and attention disorders. The EEG test took several hours, and throughout this entire time, I just pummeled our patients with personal questions about their symptoms. I was fascinated by their experiences and didn’t realize how invasive my questions were until the director of the clinic finally pulled me aside and told me to cut it out. My biggest lesson learned was about the importance of creating a psychologically safe space for others and gradually earn people’s trust. On the flip side, I do still try to hold onto the sentiment I had back then when I didn’t associate psychological experiences of any kind with shame or blame. I still try to stay curious and hold that unconditional positive regard for everyone I meet.

What advice would you give to other business leaders to help their employees to thrive and avoid burnout?

Everyone needs something different. So find ways to talk to people, hear from them, and reward them for telling the truth about what they need. A framework we teach at LifeLabs Learning that is especially helpful for diagnosing causes of burnout is called the CAMPS Model. It stands for Certainty Autonomy Meaning Progress and Social Inclusion, and it sums up our biggest drivers of engagement. When any of these areas are threatened, burnout becomes likely. To help your employees stay in the engaged ‘camp,’ audit your employee experience through the CAMPS lens and encourage your managers to ask CAMPS questions in their one-on-ones. For example: “What’s an area where you’d like more clarity or predictability?” and “How satisfied are you with your level of autonomy at work?”

Ok, let’s jump to the core of our interview. Some companies have many years of experience with managing a remote team. Others have just started this, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Can you tell us how many years of experience you have managing remote teams?

Our team was a hybrid (partially in-person, partially remote) for four years, and we’ve been fully remote for a year and a half. So we’ve had great opportunities to learn through direct experience. But we’ve also had the unique advantage of getting to interview and study our clients, many of whom have been fully remote or remote-first for years.

Managing a team remotely can be very different than managing a team that is in front of you. Can you articulate for our readers what the five main challenges are regarding managing a remote team? Can you give a story or example for each?

I personally don’t find it very different. If anything, having a remote team just nudges me to be a more deliberate, thoughtful leader. That said, the key areas that require intentional effort are:

1.Work visibility: Managers who are used to in-person work often report feeling uneasy going remote because they can’t physically see work being done. This creates delayed feedback, miscommunication, or micromanagement/trust issues.

Example: One manager we interviewed told us he was stuck in constant ‘toggle mode’ when he switched to remote work. He would find himself swinging back and forth from being too hands-off, (trying to give people total freedom) to being way too hands-on (as soon as he spotted mistakes or missed deadlines). If he didn’t see meetings on people’s calendars, he became convinced they were off on the beach somewhere — even when it was wintertime! Finally, he talked to his team about it, even sharing the beach fear. They said they also felt the stress and pressure to prove they were working, leading to long days and frustrated family members. Together, they came up with a daily huddle ritual and clearer metrics. They even started using beach Zoom backgrounds once they could laugh about how far they’d come.

The fix: Focus on outputs rather than inputs. Get aligned on what successful results are. Co-create measurable metrics, and stop worrying about whether and when people are doing their work. To avoid bad surprises, set up consistent checkpoints along the way where you can review progress together and share feedback. This practice also makes unhealthy overwork less likely, which is often triggered by the desire to prove we’re working (and can easily lead to burnout).

2. Meetings: Since so much collaboration happens through meetings, it’s especially important to get virtual meetings right. While any bad meeting is unpleasant, virtual meetings can be downright awful.

Example: The toughest meetings to lead well are hybrid meetings (when some people are in-person and some are virtual). It took us about two years to get this right at LifeLabs Learning. A real low point was trying to include our remote employees during fun/special in-person events. One time, we invited an instructor to lead a Japanese tea ceremony in our office. We placed laptops on the floor so our remote team members could feel included, but all they could see was people’s butts and hear comments about how delicious the tea was. Shortly after that, we totally changed up how we do hybrid meetings. From then on, our rule was ‘one person, one screen.’ So even if one person is remote, we all got on our laptops with cameras on. And we started holding much more remote-friendly social events!

The fix: Keep meetings short or take breaks every 15–20 minutes. Staring at a screen dries out our eyes, causing headaches and fatigue. So take quick breaks to stretch, move, and blink. Establish explicit meeting norms. Based on our research on what makes great meetings different, here are our favorites: (1) rotate meeting roles like facilitator and notetaker, (2) start with an agenda, (3) make sure every voice is heard equally by using ‘round-robins’ or asking “who haven’t we heard from on this topic yet?”

3. Communication: When at a distance, it can be easy to become frustrated by differences in people’s communication preferences. Some people prefer text messages, some like to talk face-to-face, some use Slack, some use email and some never seem to reply to their email. What’s more, asynchronous work can cause paralinguistic friction — such as a lack of clarity about what silence means or the inability to “hear” tone through written communication.

Example: At LifeLabs Learning, going fully remote has made us seriously up our GIF game. It is not usual these days for people to provide an additional emotional context for their written communication with funny GIFs, emojis, and pictures. Recently someone sent me an email that seemed surprisingly terse. I sat there staring at it for a moment, trying to make sense of the tone. Within seconds, a follow-up email appeared with a GIF of an apologizing puppy and the message: “Sorry I was so abrupt. Just short on time. Not frustrated. K. THNX. BAI.”

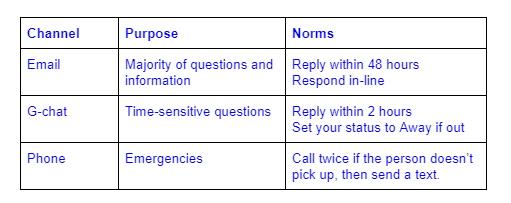

The fix: Agree to shared communication channels and norms. For example:

4. Connection: Without a deliberate dedication to building a connection, a feeling of disconnect can easily seep in. The impact is loneliness, lower trust, a higher degree of unproductive conflict, and less engagement.

Example: One of my coworkers, McKendree, is an extrovert who realized that she wasn’t getting the sense of connection she wanted in an introvert-heavy, remote team. She realized that all of our connection activities were structured (e.g., game time, skill ups), but there wasn’t much room for small talk. She created an internal event series called Purposeless Conversations that quickly became loved by many team members, including some introverts. She also has a habit of joining meetings early and ‘lingering in the virtual hallways’ once meetings wrap up for some extra casual conversation. It has now become a norm to “linger” for many folks on our team.

The fix: Keep to a consistent cadence of weekly one-on-ones. Encourage folks to keep cameras on if they can. Normalize 5 minutes for small talk at the start and end of meetings. Research shows this unstructured social time actually leads to more product meetings! And invite your team members to take turns coming up with opportunities for social connection (e.g., silent coworking time, monthly celebrations, learning days, and game time).

5. Inclusion: At a distance, our human tendency toward acting on our biases can grow even more. Without realizing it, leaders could spend more time coaching, supporting, mentoring, and just socializing with the people they already know well and spend less meaningful time invested in people they are less comfortable with. This could lead to systematic disadvantages for people who are new, who joined the company remotely, and for people with marginalized identities.

Example: At the start of the pandemic, several of us in leadership roles at LifeLabs Learning realized that we stayed in close contact with people we already knew well, but only rarely connected with our newest team members. This wasn’t only a problem for a sense of connection. It also meant we were systematically hearing ideas and providing career support for some people and not others. Since then, all of our executive team members have set up weekly virtual office hours, quarterly Ask Me Anything sessions, and monthly team member ‘roulette’ meetings via Donut.

The fix: No matter how naturally leadership comes to you, create a discipline for yourself that ensures nobody on your team gets left behind. Consider that even the best pilots still use a pre-flight checklist every single time. For example, you might want to schedule calendar blocks and reminders to hold one-on-ones, give feedback, ask for feedback, help people update their development goals, ask someone to show their work and celebrate people’s effort and results.

In my experience, one of the trickiest parts of managing a remote team is giving honest feedback, in a way that doesn’t come across as too harsh. If someone is in front of you much of the nuance can be picked up in facial expressions and body language. But not when someone is remote. Can you give a few suggestions about how to best give constructive criticism to a remote employee?

I think any feedback that could spark defensiveness should still be given face-to-face with cameras on or at the very least by tone. Our brains just can’t help layering on a negative tone to written communication. Another option is to let someone know you have feedback for them and offer them a choice of how to deliver it. For example: “Hey, I’d love to give you feedback on how that meeting went. Would you rather I send it over in writing first or should we schedule a quick meeting to talk it over?”

Can you specifically address how to give constructive feedback over email? How do you prevent the email from sounding too critical or harsh?

I would highly advise written feedback unless: (a) it’s a minor issue and unlikely to cause defensiveness, (b) the person has requested the feedback in writing. Feedback is a key tool for learning and calibration, so it’s worth it to put in that little bit of extra effort to make sure it lands well. Try starting out with what we call a micro-yes, to kick off the conversation. For example: “Would you be open to hearing my feedback about X?” or “When would be a good time for me to share my feedback on Y?” “Would it be best for me to find time on our calendars to meet or share it in writing first?”

If you do send your email in writing, use what we call the Q-BIQ method at LifeLabs Learning — based on our research on what great feedback givers do differently. Note: Q-BIQ is pronounced ‘cubic’ (think of it as a tool to expand your team’s capacity!).

Question: Can I share some feedback with you about X? Would an email work for you?

Behavior: I noticed that you [fill in specific behavior].

Impact: I mention it because [fill in why it’s important].

Question: What are your thoughts? / How do you see it?

For extra brain-friendliness, you can also add an intention statement to frame your message. For example: “The reason I share this is because I value your perspective and would love to keep improving how we work together.”

Can you share any suggestions for teams who are used to working together on location but are forced to work remotely due to the pandemic? Are there potential obstacles one should avoid with a team that is just getting used to working remotely?

I’d suggest reviewing the 5 challenges and fixes listed above. As a team, discuss how you are doing in each category. I’m a big fan of the scaling question: “On a scale of 1–10, how well do we do in each of these areas? What’s working well? What can we do this month to increase our score by 1 point in one of these categories?”

What do you suggest can be done to create a healthy and empowering work culture with a team that is remote and not physically together?

I’d again return to the CAMPS Model here since it’s such a great summary of our most important human needs:

Certainty: Clarify roles and goals as much as possible. Is everyone clear on who does what? Do we have a shared definition of success? Create rituals that give people a sense of consistency (e.g., daily huddles, weekly one-on-ones, monthly retrospectives).

Autonomy: Ask people if they would like more guidance or more decision-making power. Make sure that each person on your team has an area of ownership/something they’re in charge of.

Meaning: Ask your team members what they find most meaningful about their work, then regularly find ways to make their impact visible. This can be sharing feedback directly, passing on feedback from others, and even inviting special guests to talk about how they’ve been impacted.

Progress: Find ways to make people’s work progress visible. This can be a kanban board, checklist, or even a thermometer graphic! Don’t forget to focus on professional development progress as well. Schedule quarterly meetings to talk about career growth and weekly check-ins to reflect on the growth and decide on small steps to take next.

Social Inclusion: Creating a variety of opportunities for connection, including work connection (e.g., project show and tell) and social connection (e.g., taking a fitness class together), small group connection, and one-on-one connection. Invite your team members to take turns coming up with opportunities to get to know one another or just spend quality time together.

You are a person of great influence. If you could inspire a movement that would bring the most amount of good to the most amount of people, what would that be? You never know what your idea can trigger. 🙂

If I could inspire one perspective it would be to see all life as equal in value. There is no such thing as a more important or less important person. And there is no such thing as a more important or less important animal (humans included). If we take this thought to its logical conclusion, we could not value some groups over others, and we could not knowingly cause harm to people or animals. We could eradicate all barriers to flourishing, from racism to speciesism. And the irony is that if we could step away from a mindset of scarcity and competition, we would create more, heal more, and achieve more together. As Robin Wall Kimmerer writes, “all flourishing is mutual.”

Can you please give us your favorite “Life Lesson Quote”? Can you share how that was relevant to you in your life?

We feel most comfortable when things are certain, but we feel most alive when they’re not. This is a fact of life I think about often. It reminds me to nudge myself and others outside their comfort zones and that change is good, even when it doesn’t feel good in the moment. This concept even made its way into two of our company values at LifeLabs Learning: Always Be Learning and Choose Courage Over Comfort.

Thank you for these great insights!

Thank you for these great questions 🙂